How Stress Affects Hormonal Health

Aug 14, 2024

We ensure our content is always unique, unbiased, supported by evidence. Each piece is based on a review of research available at the time of publication and is fact-checked and medically reviewed by a topic expert.

Written by: Jayelah Bush

Medically reviewed by: Clara Sartor, ND

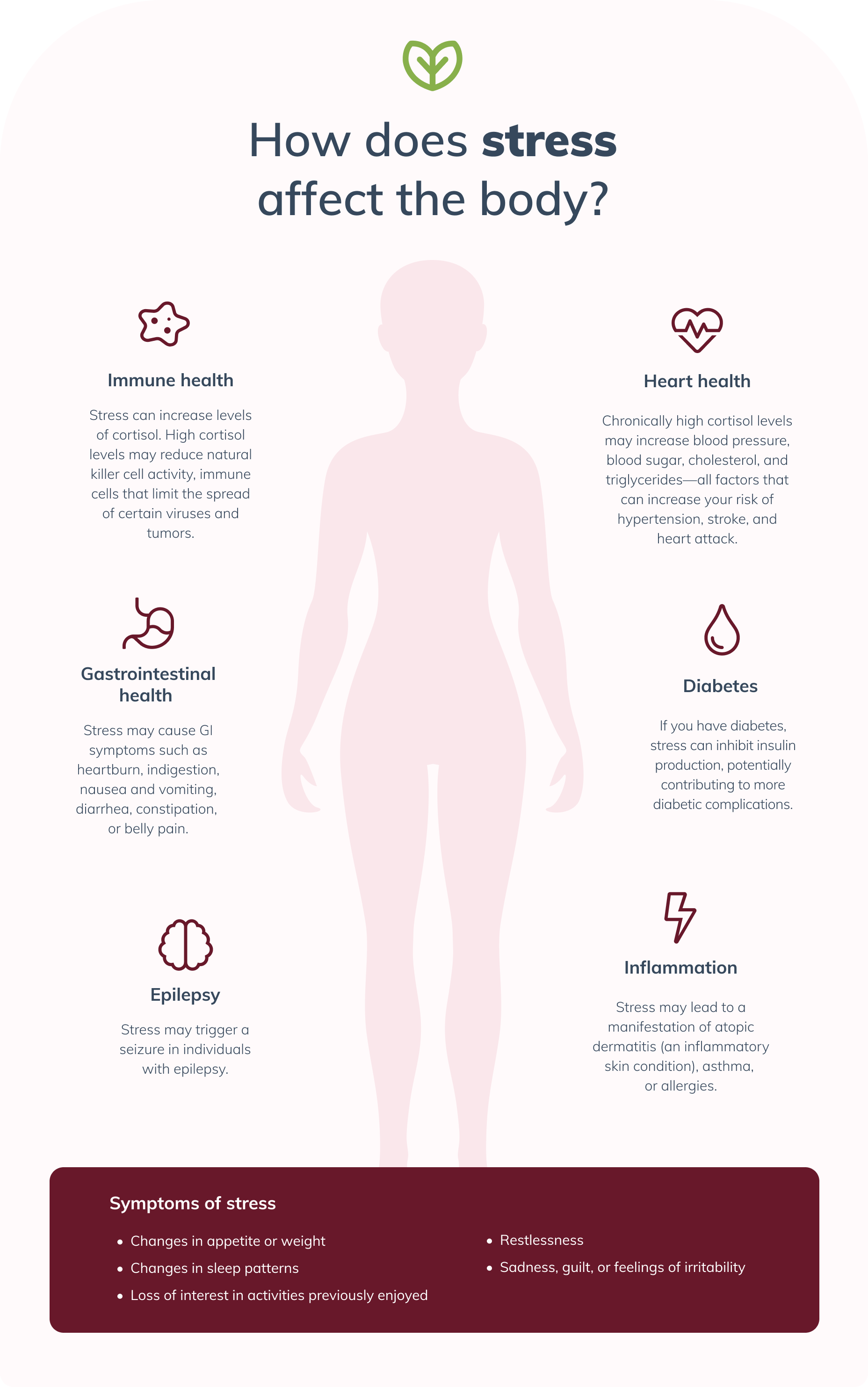

The stress response is the body’s natural reaction to situations that may be overwhelming, frustrating, or nerve-wracking. Stress begins with the brain, as it identifies stress as well as the behavioral and physiological response to take. (McEwen 2008) Hormones, such as adrenaline and cortisol, are released as a part of the stress response. (Chu 2024)

Changes in hormone levels can impact many body systems, including the immune and reproductive systems. (Ranabir 2011) Keep reading below to learn more about stress and female hormones and their role in hormone imbalance.

In response to stress, the brain triggers the fight or flight response, which causes the adrenal glands to release several hormones. The adrenals sit atop of the kidneys and are only the size of a sugar cube; weighing as much as three to four paper clips, but they can dramatically affect how we feel. (National Institutes of Health 2002) Generally, the stress response has three stages, with different hormones and hormone levels impacting each stage. Acute stress is represented by stage one, while stages two and three develop after prolonged stress.

This is the initial stage of the stress response that triggers fight or flight-related body changes. Hormones that increase adrenaline (epinephrine and norepinephrine) are released as an immediate response to a stressor. These hormones put the body in fight or flight mode by:

These bodily changes make you feel alarmed, alert, and reactive, and allow you to perform more strenuous activity than normal. (Chu 2024)

At the same time as adrenaline kicks in, cortisol release is being triggered at a slower, yet timely, rate. Cortisol supports the effects of adrenaline by signaling the body to conserve energy and dedicate resources to the stress response. Cortisol suppresses the immune system, which restricts the growth and healing of cells and wounds. (Chu 2024)

When the brain communicates that the stressor is gone, cortisol release should stop and the effects of stress hormones should begin to subside. (National Institutes of Health 2002)

If stress is repeated or ongoing, the body adapts to sustain its heightened state. The immune system remains suppressed and other organ systems begin to adapt to stress too. The digestive system will adapt to this high-stress state by decreasing hunger cues and using less energy for digestion, for example. This can speed up digestion time and limit nutrient absorption.

Remaining in a constantly stressed state can cause fatigue and negatively affect focus, memory, and mood. (Chu 2024)

Long-term hormonal imbalances related to cortisol and other stress hormones are exhausting on the body. Other functional and chemical changes occur to help maintain this stressed state. Body systems that rely on hormones, such as the reproductive system, begin to lose optimal function. (Chu 2024)(Tsigos 2020) Increased anxiety, depression, hunger, and fatigue may occur. (Chu 2024)(van Loenen 2020)

Chronic stress keeps cortisol levels high, which may cause high blood pressure and reduced immunity. (McEwen 2008)

Chronic stress keeps cortisol levels high, which may cause high blood pressure and reduced immunity. (McEwen 2008)

Hormones from the endocrine system are involved in necessary processes related to virtually every organ in the body. Endocrine glands, such as the adrenal gland, ovaries, and thyroid glands, produce and release hormones into the bloodstream. (National Cancer Institute) From digestive hormones to sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen, stress can impact hormonal balance. This can interrupt normal body functions and cause emotional, mental, and physical symptoms. (Ranabir 2011)

Ghrelin is a hormone that regulates our appetite by stimulating hunger. Ghrelin levels increase when the body is in an energy loss or during extended periods of stress. (Chuang 2010)(van Loenen 2020)

Ghrelin increases hunger frequency, reduces the use of body fat for energy, and increases the use of carbohydrates (sugars). Ghrelin also promotes the secretion of other metabolic hormones, including growth hormone and insulin. Extended periods of high ghrelin levels increase food intake and fat accumulation, which may lead to weight gain. (Campbell 2022)(Chuang 2010)(Ranabir 2011)

After eating, food and beverages are broken down in the digestive tract and enter the bloodstream as glucose (sugar) to be used as energy by tissues and organs. The hormone insulin is secreted by the pancreas to facilitate this process. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2019) During periods of stress, insulin secretion is reduced, which can leave blood sugar levels high. This may contribute to the development of type 2 diabetes or worsen symptoms in those already with the condition. (Tsigos 2020)(Wong 2019)

Did you know? Chronic (long-term) stress can make the body insulin resistant. Insulin resistance occurs when cells lose their sensitivity to insulin, which leads to higher blood sugar levels. (Yan 2016)

Maintaining thyroid hormonal balance is important for metabolism and childhood growth and development. Thyroid hormone increases the resting metabolic rate, which is the amount of energy needed only for the body’s basic functions, such as maintaining an adequate core body temperature. The thyroid’s influence on energy storage and use supports growth in youth and the maintenance of good health in adulthood. A thyroid that's excessively active or not active enough can lead to hormonal imbalances. (Helmreich 2011)

Research indicates that during stress, thyroid activation is decreased, as more energy is directed to the stress response. (Frick 2009)(Helmreich 2011)(Walter 2012) This may negatively impact the thyroid long-term, triggering or worsening thyroid-related autoimmune conditions such as Grave’s disease or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. (Helmreich 2011) Suppressing thyroid production long-term may lead to symptoms such as fatigue, fertility difficulties, and weight gain. (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases 2022)

Exercise is good for maintaining a healthy weight, releasing stress, and supporting hormonal health. (National Library of Medicine)

Exercise is good for maintaining a healthy weight, releasing stress, and supporting hormonal health. (National Library of Medicine)

Gonadotropin (reproductive) hormones act on the gonads (reproductive glands) to induce sex hormone production. During the stress response, the release of gonadotropins is suppressed. (Ranabir 2011) This can disrupt normal reproductive function and hormone production, potentially causing a variety of symptoms, including:

Healthy lifestyle habits, including eating a balanced diet, staying active, and maintaining body weight, are effective strategies for balancing hormones. It’s also important to practice healthy stress management techniques to reduce cortisol levels and sensitivity to stress. (Ranabir 2011) Meditation, physical activity, and social support may help reduce the symptoms of stress. (American Psychological Association 2019)

There are also many supplements that may help with stress. Adaptogens like ashwagandha and rhodiola may have the ability to improve stress tolerance and reduce major functional changes related to stress. (Panossian 2009)

Stress has a significant impact on hormones, which need to be balanced for optimal health. Chronic stress can wreak havoc throughout the body, including the immune and reproductive systems. Hormonal imbalances can impact many functions, including the ability to maintain a healthy weight, conceive a baby, and tolerate stress. Reducing stress levels with healthy lifestyle habits such as meditation and regular physical activity may help reduce hormonal imbalances caused by stress.

As a healthcare provider, you can determine your patients’ hormone levels using a simple blood, urine, or saliva test.

References

American Psychological Association. (2019). 11 healthy ways to handle life’s stressors. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/tips

Abizaid, A. (2019). Stress and obesity: The ghrelin connection. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 31(7).

Campbell M, Jialal I. Physiology, Endocrine Hormones. [Updated 2022 Sep 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538498/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019, August 12). The Insulin Resistance–Diabetes Connection. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/insulin-resistance.html

Chu B, Marwaha K, Sanvictores T, et al. Physiology, Stress Reaction. [Updated 2024 Sep 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541120/

Chuang, J. C., & Zigman, J. M. (2010). Ghrelin’s roles in stress, mood, and anxiety regulation. International Journal of Peptides, 2010, 1–5.

Frick, L. R., Rapanelli, M., Bussmann, U. A., Klecha, A. J., Arcos, M. L. B., Genaro, A. M., & Cremaschi, G. A. (2009). Involvement of thyroid hormones in the alterations of T-cell immunity and tumor progression induced by chronic stress. Biological Psychiatry, 65(11), 935–942.

Helmreich, D. L., & Tylee, D. (2011). Thyroid hormone regulation by stress and behavioral differences in adult male rats. Hormones and Behavior, 60(3), 284–291.

McEwen, B. S. (2008). Central effects of stress hormones in health and disease: Understanding the protective and damaging effects of stress and stress mediators. European Journal of Pharmacology, 583(2–3), 174–185.

Mullur, R., Liu, Y. Y., & Brent, G. A. (2014). Thyroid hormone regulation of metabolism. Physiological Reviews, 94(2), 355–382.

National Cancer Institute. (n.d.). NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/endocrine-system

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2022, November 16). Hypothyroidism (Underactive Thyroid). https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/endocrine-diseases/hypothyroidism

National Institutes of Health. (2002). Stress system malfunction could lead to serious, life threatening disease. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/newsroom/releases/stress

National Library of Medicine. (n.d.). Benefits of Exercise. https://medlineplus.gov/benefitsofexercise.html

Office on Women’s Health. (n.d.). Stress and your health. https://www.womenshealth.gov/mental-health/good-mental-health/stress-and-your-health

Panossian, A., Wikman, G., Kaur, P., & Asea, A. (2009). Adaptogens exert a stress-protective effect by modulation of expression of molecular chaperones. Phytomedicine, 16(6–7), 617–622.

Ranabir, S., & Reetu, K. (2011). Stress and hormones. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 15(1), 18.

Tsatsoulis, A. (2006). The role of stress in the clinical expression of thyroid autoimmunity. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1088(1), 382–395.

Tsigos C, Kyrou I, Kassi E, et al. Stress: Endocrine Physiology and Pathophysiology. [Updated 2020 Oct 17]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278995/

van Loenen, M. R., Geenen, B., Arnoldussen, I. A. C., & Kiliaan, A. J. (2020). Ghrelin as a prominent endocrine factor in stress-induced obesity. Nutritional Neuroscience, 25(7), 1413–1424.

Walter, K. N., Corwin, E. J., Ulbrecht, J., Demers, L. M., Bennett, J. M., Whetzel, C. A., & Klein, L. C. (2012). Elevated thyroid stimulating hormone is associated with elevated cortisol in healthy young men and women. Thyroid Research, 5(1).

Wong, H., Singh, J., Go, R. M., Ahluwalia, N., & Guerrero-Go, M. A. (2019). The Effects of mental stress on non-insulin-dependent diabetes: Determining the relationship between catecholamine and adrenergic signals from stress, anxiety, and depression on the physiological changes in the pancreatic hormone secretion. Cureus.

Yan, Y. X., Xiao, H. B., Wang, S. S., Zhao, J., He, Y., Wang, W., & Dong, J. (2016). Investigation of the relationship between chronic stress and insulin resistance in a Chinese population. Journal of epidemiology, 26(7), 355–360.