Using Cardiovascular Testing to Tell the Story of Heart Health

Aug 13, 2024

We ensure our content is always unique, unbiased, supported by evidence. Each piece is based on a review of research available at the time of publication and is fact-checked and medically reviewed by a topic expert.

Written by: Kyla Reda

Medically reviewed by: Lara Zakaria PharmD, CNS, IFMCP

As the leading cause of death in the United States, there's ample focus and research on cardiovascular disease. The condition, affecting both men and women across various racial and ethnic groups, has been linked to one in five deaths, so the importance of cardiovascular testing has never been clearer.

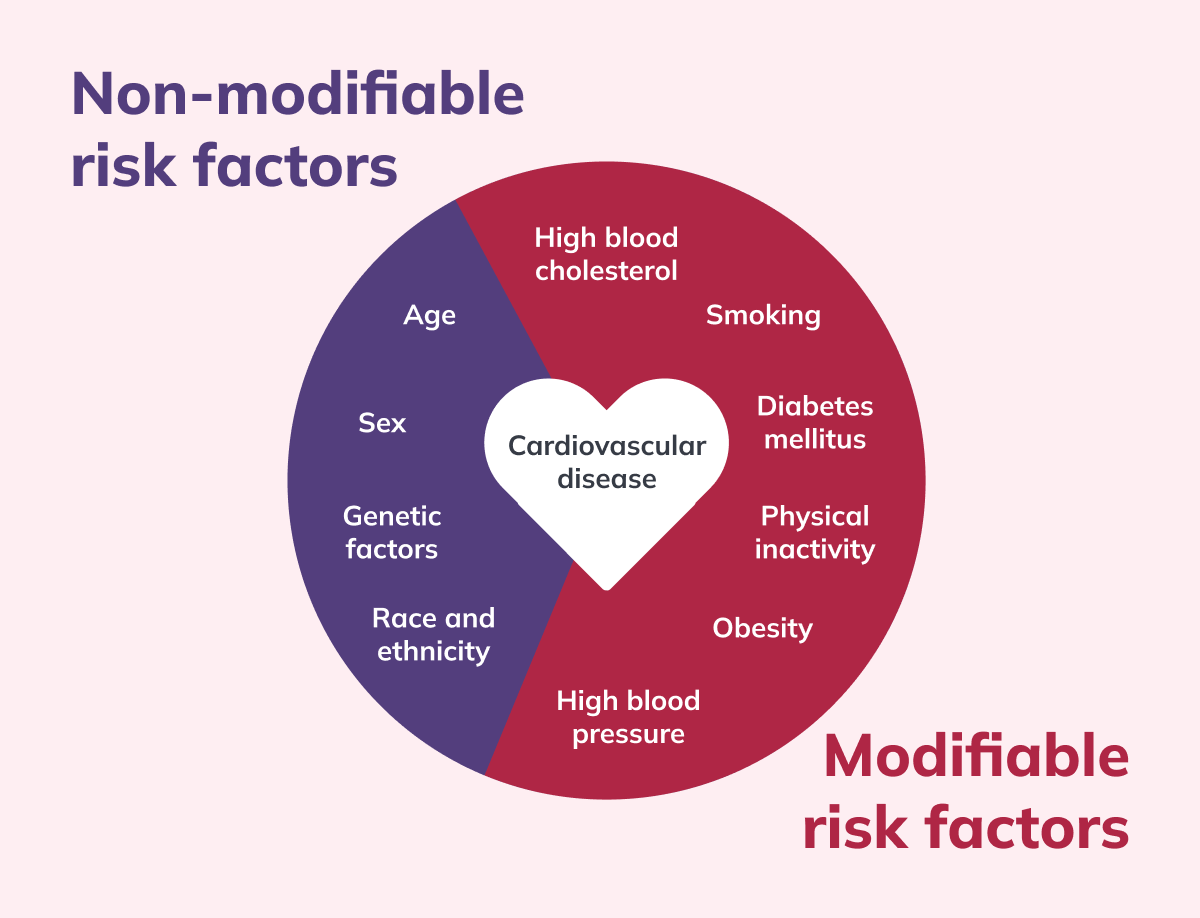

Unlike many common conditions, cardiovascular disease is considered preventable and treatable. Many risk markers can be clearly assessed, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking. Nearly half the people in the United States have at least one of these risk factors. Blood tests assessing everything from lipids and cardiac enzymes to full metabolic panels can be a tool for practitioners to help patients better understand overall cardiovascular health and risks.

Did you know? One person dies from cardiovascular disease every 33 seconds—or in about the time it took to read that last paragraph. (CDC 2024)

As a practitioner, you have several options for cardiovascular testing and assessing heart health. Finding the right mix of diagnostic labs can help you paint a clearer picture for your patients. Every year, there are more than 800,000 heart attacks in the United States (CDC 2024) and almost as many strokes. (CDC 2024) It’s never too early to assess your patients’ risk and discuss prevention strategies. Cardiovascular testing is one of a practitioner's most effective tools to establish a baseline and begin that conversation. Here are some of the most commonly utilized cardiac screening blood tests.

While it’s likely your patients are familiar with the concept of cholesterol, there's a chance they're confused by it as well. (Goldman 2006) This simple blood test provides a comprehensive assessment and breakdown of the different types of lipids in the blood: low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglycerides. (HealthDirect 2022) Research has consistently shown that lipid levels, particularly LDL and HDL, are indicators of cardiovascular risk. Assessing levels and discussing the interplay between “good” cholesterol and “bad” cholesterol is important in promoting cardiovascular health. (American Heart Association 2024) For more accurate results, it's recommended that patients fast for 10–12 hours prior to blood draw. (Nigam 2011)

Lipid profiles are also beneficial when measuring the efficacy of a treatment plan, providing healthcare providers and patients with a detailed view of changes in cholesterol levels.

While traditional risk factors have been well established over the years, new studies point to a connection between low-grade inflammation and cardiovascular disease. (Amezcua-Castillo 2023) C-reactive protein (CRP), a substance produced by the liver, is a known biomarker of inflammation. Inflammation in the arteries can be a key factor in the development of atherosclerosis, also known as the buildup of arterial plaque. Monitoring inflammation with a CRP blood test can help practitioners assess the risk of cardiovascular disease, especially in borderline cases or where traditional risk algorithms may not fully capture the complexities of an individual patient. (Amezcua-Castillo 2023) (Han 2022) (MedlinePlus n.d.)

Moreover, the high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) test can detect lower levels of inflammation than the standard CRP test. This enhanced sensitivity makes hs-CRP crucial for identifying higher cardiovascular risk in patients without other risk factors. By measuring subtle increases in inflammation, hs-CRP refines risk assessment and helps tailor preventive strategies.

This amino acid is produced during the body’s metabolism of methionine to cysteine. Elevated levels of homocysteine in the blood can be linked to cardiovascular endothelial damage and structural changes in the arteries. While further studies are required to determine whether elevated homocysteine is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease or merely a biomarker of the condition, assessing levels can provide additional insight into cardiovascular health. (Ganguly 2015) (Leatham 2024) (MedlinePlus n.d.) (Son 2022)

One of the most common diagnostic labs available, (MedlinePlus n.d.) this routine blood test measures 14 different substances in the blood including glucose, electrolytes (e.g., calcium, sodium, potassium, carbon dioxide, chloride), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, albumin, and total protein. It provides vital information about cardiovascular health and metabolism. Elevated blood glucose levels can indicate a risk of cardiovascular disease, (NIDDK 2021) and it’s been shown that balanced electrolyte levels can help the heart function properly. (Bennett 2020)

The following tests are useful to consider for patient evaluations. They can be used in addition to basic tests to enhance assessments.

A1C testing measures the average blood glucose levels over the past three months. The higher the glucose level in the bloodstream, the more it'll attach to the hemoglobin. This test can be useful for identifying and monitoring insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and prediabetes, along with diabetes. (NIDDK 2018)

Lipoprotein Fractional NMR testing can help assess the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with elevated risk based on traditional or emerging factors. It can also be useful in assessing a response in patients undergoing lipid-lowering therapy. NMR lipoprofile testing provides a detailed analysis of lipoprotein particles, offering insights beyond basic lipid testing by quantifying the size and number of these particles. This method gives a more robust risk assessment for cardiovascular disease, especially in patients with complex lipid profiles, helping tailor therapeutic approaches to individual patient needs. (Starich 2020)

Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) testing measures the amount of this specific protein that attaches to LDL cholesterol. ApoB can help transport the substances that contribute to plaque buildup in the arteries. By measuring ApoB levels, providers can assess the actual burden of atherogenic lipoproteins, offering a clearer indicator of cardiovascular risk than traditional cholesterol tests alone. This makes ApoB testing a valuable tool in predicting and managing cardiovascular disease. (Sniderman 2019)

Lipoprotein (a) (Lp(a)) testing can provide a deeper understanding of risk than routine cholesterol tests alone. If a large percentage of LDL is carried by lipoprotein (a) particles, the risk of heart disease and stroke could be elevated. (MedlinePlus n.d.) Lp(a) testing identifies the presence of lipoprotein (a) particles – which carry LDL cholesterol – and are associated with substantially higher risk for heart disease. By focusing on these particles, clinicians can gain a more precise assessment of cardiovascular risk beyond what standard cholesterol tests offer.

While some risk factors for cardiovascular health are out of a patient's control, several can be addressed with lifestyle modifications.

While some risk factors for cardiovascular health are out of a patient's control, several can be addressed with lifestyle modifications.

Assessing cardiovascular health is the first step toward promoting better outcomes. While some risk factors are beyond a patient’s control, working on those lifestyle factors that can be modified can significantly reduce cardiovascular risk. Helping patients take a series of small but smarter steps regarding diet, exercise, sleep, and stress can be challenging but can lead to significantly better outcomes.

Increasing physical activity benefits cardiovascular health in multiple ways—from lowering blood pressure and triglycerides to raising “good” cholesterol levels. It also helps patients maintain a healthy weight and reduce stress. Remind patients the goal isn’t running a marathon tomorrow but adding more activity to their daily routine. This can start with a 20 or 30-minute brisk walk three times a week and build from there. (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2022)

It’s not news that the food we eat is critical to cardiovascular health. However, it's important to remember that numerous socioeconomic factors can play a role in a patient’s diet, and access to fresh fruits, vegetables, and lean proteins isn't guaranteed. Help patients avoid highly processed and fatty foods by finding heart-healthy alternatives that work within their budget and lifestyle. (Anand 2015)

Among the most effective dietary interventions are the Mediterranean (Martínez-González 2019) and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diets, (Shoaibinobarian 2023) both of which are rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins, and have been extensively studied for their benefits in reducing cardiovascular disease risk and managing cholesterol levels. Encouraging the inclusion of omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish like salmon, and fiber-rich foods can also play a crucial role in lowering cholesterol and improving overall heart health. (Mohebi-Nejad 2014) These diet modifications help manage health risks and are adaptable to various economic situations, making them practical options for diverse populations.

We all know that adults require around seven hours of sleep each night, yet one-third of people report not getting enough sleep. Sleep reduces nocturnal blood pressure by 10–20%; without this daily dip, studies indicate an increased risk of potential cardiovascular disease. (Calhoun 2010) Still, there are only so many hours in the day, so work with your patients to help them understand the importance of good sleep. (CDC 2024)

Mental health is more than a popular headline. Studies have identified stress as an emerging factor for cardiovascular risk, even in individuals who lack the traditional risk profile. (Vancheri 2022) While there are several potential sources of stress—work, relationships, economics, etc.—they all share a common combination of external pressures that meet physiological inabilities to cope with said stressors. Compounding the physical effects of stress, such as elevated blood pressure, are the second-order effects on well-being. When people are stressed, they tend to lose sleep, make bad food choices, exercise less, and consume more alcohol. (Anthenelli 2012) (Vancheri 2022)

Providing patients with the knowledge behind the numbers of their cardiovascular testing can pave the way for better treatment adherence.

Providing patients with the knowledge behind the numbers of their cardiovascular testing can pave the way for better treatment adherence.

Battling the risk of heart disease should begin by getting patients to focus on their heart health. The silver lining remains a practitioner's ability to assess risk through regular cardiovascular testing and promote better outcomes through thoughtful lifestyle modifications. Now that we know what is included in cardiovascular screening and the benefits of the various diagnostic labs, we can continue the work of educating patients on making better lifestyle choices to reduce their risk factors. By explaining the results of a lipid profile or the potential impact of high blood glucose in a comprehensive metabolic panel, practitioners can help shine a light on these prevalent but potentially avoidable conditions.

References

About sleep and your heart health. (2024, May 15). Heart Disease. https://www.cdc.gov/heart-disease/about/sleep-and-heart-health.html

Amezcua-Castillo, E., González-Pacheco, H., Martín, A. S., Méndez-Ocampo, P., Gutierrez-Moctezuma, I., Massó, F., Sierra-Lara, D., Springall, R., Rodríguez, E., Arias-Mendoza, A., & Amezcua-Guerra, L. M. (2023). C-Reactive Protein: The Quintessential Marker of Systemic Inflammation in Coronary Artery Disease—Advancing toward Precision Medicine. Biomedicines, 11(9), 2444. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11092444

Anand, S. S., Hawkes, C., De Souza, R. J., Mente, A., Dehghan, M., Nugent, R., Zulyniak, M. A., Weis, T., Bernstein, A. M., Krauss, R. M., Kromhout, D., Jenkins, D. J., Malik, V., Martinez-Gonzalez, M. A., Mozaffarian, D., Yusuf, S., Willett, W. C., & Popkin, B. M. (2015). Food Consumption and its Impact on Cardiovascular Disease: Importance of Solutions Focused on the Globalized Food System. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 66(14), 1590–1614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.050

Anthenelli, R., & Grandison, L. (2012). Effects of stress on alcohol consumption. Alcohol research: current reviews, 34(4), 381–382. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3860387/

Benefits | NHLBI, NIH. (2022, March 24). NHLBI, NIH. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/heart/physical-activity/benefits

Bennett, J., Deslippe, A. L., Crosby, C., Belles, S., & Banna, J. (2020). Electrolytes and cardiovascular disease risk. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 14(4), 361–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827620915708

Calhoun, D. A., & Harding, S. M. (2010). Sleep and hypertension. Chest, 138(2), 434–443. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.09-2954

Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (CMP). (n.d.). https://medlineplus.gov/lab-tests/comprehensive-metabolic-panel-cmp/

C-Reactive Protein (CRP) test. (n.d.). https://medlineplus.gov/lab-tests/c-reactive-protein-crp-test/

Diabetes, Heart Disease, & Stroke. (2023, June 7). National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/preventing-problems/heart-disease-stroke

Ganguly, P., & Alam, S. F. (2015). Role of homocysteine in the development of cardiovascular disease. Nutrition Journal, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-14-6

Goldman, R. E. (2006). Patients’ perceptions of cholesterol, cardiovascular disease risk, and risk communication strategies. Annals of Family Medicine, 4(3), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.534

Han, E., Fritzer-Szekeres, M., Szekeres, T., Gehrig, T., Gyöngyösi, M., & Bergler-Klein, J. (2022). Comparison of High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein vs C-reactive Protein for Cardiovascular Risk Prediction in Chronic Cardiac Disease. The Journal of Applied Laboratory Medicine, 7(6), 1259–1271. https://doi.org/10.1093/jalm/jfac069

HDL (Good), LDL (Bad) cholesterol and triglycerides. (2024, February 19). www.heart.org. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/cholesterol/hdl-good-ldl-bad-cholesterol-and-triglycerides

Healthdirect Australia. (n.d.). Cholesterol and lipid tests. https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/cholesterol-and-lipid-tests#

Heart Disease Facts. (2024, May 15). Heart Disease. https://www.cdc.gov/heart-disease/data-research/facts-stats/index.html

Homocysteine test. (n.d.). https://medlineplus.gov/lab-tests/homocysteine-test/

Leatham, E. (2024, May 1). Is an elevated Homocysteine causing your heart disease? | Surrey Cardiovascular Clinic. Surrey Cardiovascular Clinic. https://www.scvc.co.uk/metabolic-health/is-an-elevated-homocysteine-causing-your-heart-disease/

Lipoprotein (A) blood test. (n.d.). https://medlineplus.gov/lab-tests/lipoprotein-a-blood-test/

Martínez-González, M. A., Gea, A., & Ruiz-Canela, M. (2019). The Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular health. Circulation Research, 124(5), 779–798. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.118.313348

Mohebi-Nejad, A., & Bikdeli, B. (2014). Omega-3 supplements and cardiovascular diseases. Tanaffos, 13(1), 6–14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4153275/

Nigam, P. K. (2010). Serum lipid profile: fasting or non-fasting? Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry, 26(1), 96–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12291-010-0095-x

Shoaibinobarian, N., Danehchin, L., Mozafarinia, M., Hekmatdoost, A., Eghtesad, S., Masoudi, S., Mohammadi, Z., Mard, A., Paridar, Y., Abolnezhadian, F., Malihi, R., Rahimi, Z., Cheraghian, B., Mir-Nasseri, M. M., Shayesteh, A. A., & Poustchi, H. (2023). The association between DASH diet adherence and cardiovascular risk factors. International Journal of Preventive Medicine/International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.ijpvm_336_21

Sniderman, A. D., Thanassoulis, G., Glavinovic, T., Navar, A. M., Pencina, M., Catapano, A., & Ference, B. A. (2019). Apolipoprotein B particles and cardiovascular disease. JAMA Cardiology, 4(12), 1287. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2019.3780

Son, P., & Lewis, L. (2022, May 8). Hyperhomocysteinemia. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554408/

Starich, M. R., Tang, J., Remaley, A. T., & Tjandra, N. (2020). Squeezing lipids: NMR characterization of lipoprotein particles under pressure. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids, 228, 104874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2020.104874

Stroke Facts. (2024, May 15). Stroke. https://www.cdc.gov/stroke/data-research/facts-stats/

The A1C Test & Diabetes. (2023, April 11). National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diagnostic-tests/a1c-test

Vancheri, F., Longo, G., Vancheri, E., & Henein, M. Y. (2022). Mental Stress and Cardiovascular Health—Part I. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(12), 3353. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11123353