Key Components of a Comprehensive Cardiovascular Assessment

Aug 16, 2024

We ensure our content is always unique, unbiased, supported by evidence. Each piece is based on a review of research available at the time of publication and is fact-checked and medically reviewed by a topic expert.

Written by: Nada Ahmed

Medically reviewed by: Lara Zakaria PharmD, CNS, IFMCP

A comprehensive cardiovascular assessment involves a thorough evaluation of various factors to accurately gauge an individual’s heart health and risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). This assessment typically includes traditional measures such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and family history, combined with laboratory testing. In addition to standard evaluations, advanced diagnostic tools like lipid particle testing, inflammatory markers, and imaging studies can help clinicians gain deeper insights into cardiovascular risks.

This holistic approach allows for the identification of subtle risk factors that may not be evident through standard tests alone, enabling more precise risk stratification and the development of tailored and effective treatment plans. This article offers a summary of key factors to consider for a thorough cardiovascular assessment.

Age, biological sex, and ethnicity significantly influence cardiovascular risk through various biological and lifestyle factors. As people age, their cardiovascular risk increases due to the natural stiffening of arteries, higher cholesterol levels, and a greater likelihood of developing conditions such as hypertension and diabetes. (Rodgers 2019) Sex plays a crucial role, as men generally have higher cardiovascular risk and tend to experience cardiovascular events earlier in life than women. (AHA 2024) Women’s risk rises substantially after menopause due to hormonal changes that affect cholesterol levels. (Rodgers 2019) Ethnicity also affects cardiovascular risk, as certain groups face higher risks due to genetic, cultural, and lifestyle factors. For instance, Black, South Asian, and Mexican Americans are at higher risk for CVD. (AHA 2024)

Recognizing these demographic influences helps in tailoring more effective preventive and treatment strategies for CVD.

Anthropometric measures like body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and blood pressure provide valuable insights into an individual’s health, particularly in relation to cardiometabolic health. Each of these measures can be used to assess cardiovascular risk and help monitor patient outcomes.

Determining BMI and waist circumference can help assess cardiovascular risk as these values can provide insight into a person’s weight and overall health. BMI may help to identify whether a person is underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese, which is important, as obesity is associated with an increased risk of CVD. However, since BMI doesn’t differentiate between muscle mass and fat mass and doesn’t account for demographic measures, which can affect body composition, relying on BMI measurements may lead to inaccurate categorization of a person’s weight.

A more useful measure to assess cardiovascular risk is waist circumference. Waist circumference specifically measures abdominal fat, which is a key indicator of visceral fat—fat stored around the organs that's more closely linked to metabolic disorders and cardiovascular risk than subcutaneous fat. Elevated waist circumference is associated with a higher risk of developing hypertension and atherosclerosis. (Cheng 2022)(Mohammadi 2020) A waist circumference greater than 40 inches in men or 35 inches in women would indicate increased risk. This measure is particularly important because abdominal fat has been shown to have a more significant impact on cardiovascular health than overall body weight alone. (Rexrode 1998)

Regular blood pressure monitoring can help detect hypertension early, enabling timely intervention and reducing cardiovascular risk.

Regular blood pressure monitoring can help detect hypertension early, enabling timely intervention and reducing cardiovascular risk.

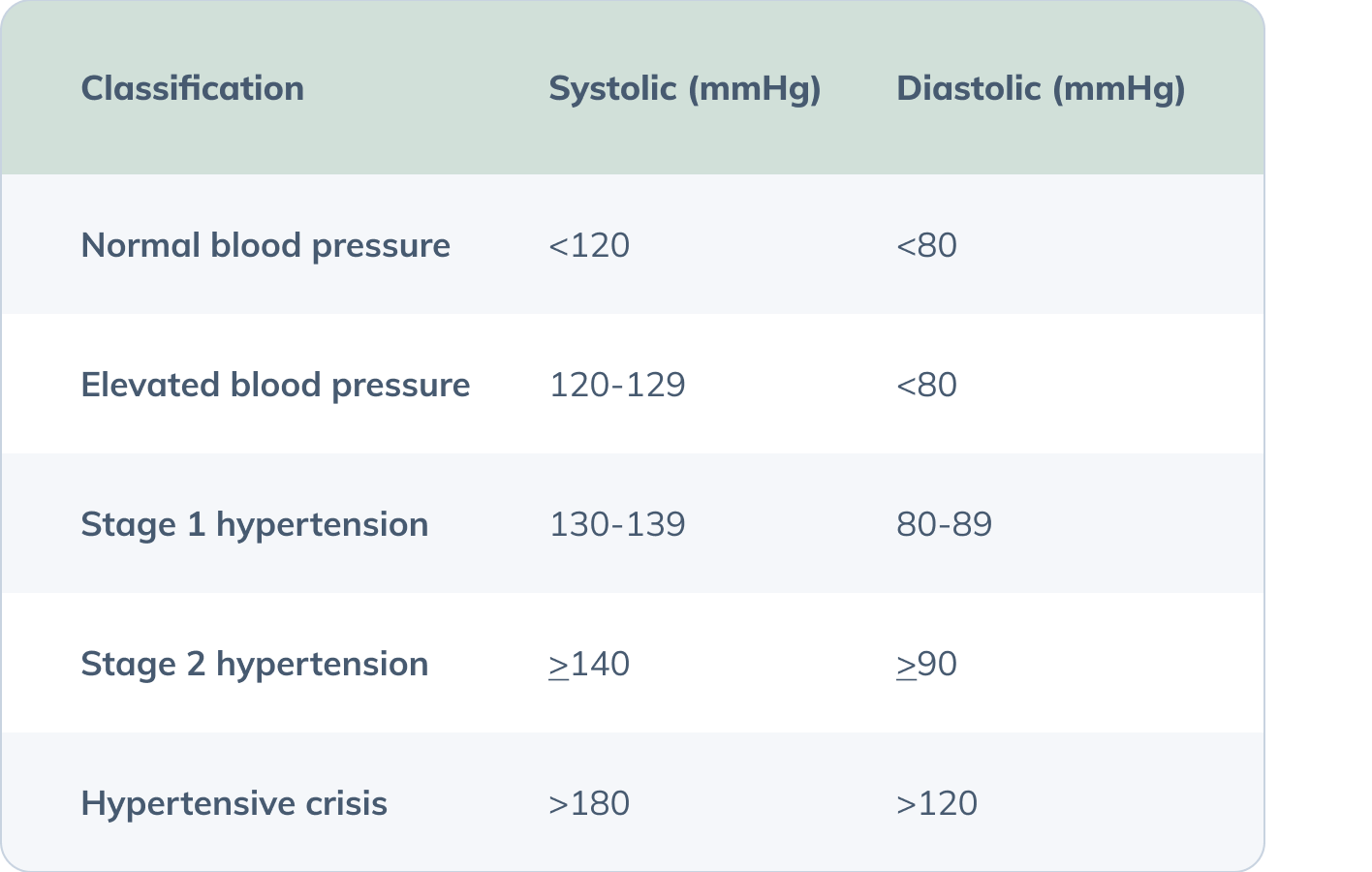

Measuring a patient’s blood pressure is crucial because hypertension often presents with no noticeable symptoms, making it a "silent" condition. Many individuals with high blood pressure are unaware of their condition until significant damage has occurred. Regular blood pressure monitoring can help detect hypertension early, allowing for timely intervention and management before it leads to serious complications. This proactive approach is especially important given that hypertension can cause gradual damage to vital organs without any immediate signs or symptoms. The following classification for blood pressure is derived from the American Heart Association.

(Flack 2020)

(Flack 2020)Determining comorbidities is a crucial aspect of cardiovascular assessment because the presence of additional health conditions can significantly influence an individual’s cardiovascular risk and overall treatment strategy. Comorbidities such as hypertension often coexist with CVD and can exacerbate cardiovascular risk. Metabolic conditions such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and thyroid disease can serve as risk-enhancing factors for cardiovascular events. (AHA 2024) Furthermore, chronic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or HIV/AIDS, as well as a history of preeclampsia or early menopause, can also increase cardiovascular risk. (AHA 2024) By thoroughly assessing and addressing comorbidities, healthcare providers can improve patient outcomes and reduce the risk of adverse events.

Considering family history in the assessment of CVD risk is essential because genetic predisposition plays a significant role in an individual’s likelihood of developing cardiovascular conditions. A family history of CVD can indicate a higher risk due to inherited genetic factors that influence cholesterol levels, blood pressure, and other key aspects of cardiovascular health. (Heart Foundation n.d.) A family history of early-onset heart disease may prompt earlier and more frequent screenings, lifestyle modifications, and genetic testing.

Assessing diet and lifestyle is critical in cardiovascular assessment because these factors have a profound impact on cardiovascular health and can significantly influence the risk of developing heart disease. Diet and lifestyle choices directly affect several key risk factors for CVD, including blood pressure, cholesterol levels, weight, and glucose metabolism.

By incorporating these aspects into cardiovascular risk assessments, healthcare providers can develop more comprehensive and effective prevention and treatment strategies. Addressing diet and lifestyle factors helps in managing cardiovascular risk more holistically, leading to better health outcomes and improved quality of life.

A diet high in saturated fats, trans fats, and refined sugars can lead to elevated cholesterol levels, increased blood pressure, and weight gain, all of which contribute to cardiovascular risk. Conversely, a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats can help manage cholesterol levels, reduce inflammation, and maintain a healthy weight. (Feingold 2024)

Similarly, lifestyle factors such as physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption play crucial roles in cardiovascular health. Regular exercise helps lower blood pressure, improve lipid profiles, and reduce the risk of obesity and diabetes, while smoking and excessive alcohol consumption are associated with higher cardiovascular risk. Stress is another important factor as chronic stress can lead to increased blood pressure, unhealthy eating habits, and a higher risk of cardiovascular events. (Vaccarino 2024) Sleep quality is important to consider as well as poor sleep can lead to weight gain, hypertension, and insulin resistance, all of which contribute to CVD. (Colten 2006)

Furthermore, inquiring about a patient’s occupational exposure is important as long-term exposure to environmental pollutants and harmful substances can also impact cardiovascular health. For example, exposure to heavy metals, pesticides, and endocrine-disrupting chemicals (e.g., bisphenol A) has been associated with the risk of CVD. (Yim 2022)(Yang 2020)

Assessing diet and lifestyle factors is critical for cardiovascular health as they significantly influence risk factors like blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and overall heart function.

Assessing diet and lifestyle factors is critical for cardiovascular health as they significantly influence risk factors like blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and overall heart function.

Certain medications and supplements can contribute to cardiovascular risk factors, making it crucial to evaluate their potential impact on your patient’s condition. For example, oral contraceptives and immunosuppressants such as cyclosporine may cause hypertension and negatively impact lipoprotein metabolism (i.e., increase triglycerides and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)). (Herink 2018)(NIH n.d.) Corticosteroids can have numerous adverse effects, including altered glucose metabolism, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. (NIH n.d.)(Wofford 2006) Antidepressants like monoamine oxidase inhibitors can lead to hypertension and are associated with the greatest weight gain. Even some medications for hypertension can have adverse effects on metabolic health. For instance, thiazide diuretics can contribute to insulin resistance and increase LDL and triglycerides. (Wofford 2006) Since certain medications have the potential to elevate cardiometabolic risk, it's crucial for healthcare providers to carefully consider the risks and benefits and explore whether alternative options might be more suitable.

Furthermore, certain constituents in herbs can also affect blood pressure and are therefore important to consider. For example, glycyrrhizin contained in licorice root can increase blood pressure. Other herbs that may cause or exacerbate hypertension include arnica, bitter orange, blue cohosh, dong quai, ephedra, ginkgo, ginseng, guarana, pennyroyal oil, Scotch broom, senna, southern bayberry, St. John's wort, and yohimbine. (Jalili 2013)

Standard lipid panels are fundamental in the initial assessment of cardiovascular risk as they provide essential information about key lipid levels in the blood. They typically measure total cholesterol, LDL, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglycerides. Elevated levels of LDL cholesterol and triglycerides, along with low levels of HDL cholesterol, are well-established risk factors for CVD. This initial assessment helps identify individuals with increased cardiovascular risk.

Standard lipid panels, however, may have limitations in fully capturing cardiovascular risk. They don’t provide detailed insights into the size, number, and composition of lipoprotein particles, which can significantly impact cardiovascular risk. Advanced lipid testing offers additional value by evaluating factors such as LDL particle number, LDL particle size, and other specific lipid subtypes. Elevated levels of particular advanced lipid markers (e.g., LDL particle number, ApoB, ApoB/ApoA1 ratio) may offer better prognostic potential than standard lipid tests. (Feingold 2023)(Paunica 2023) Other useful relevant markers like Lp(a), homocysteine, and trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) are independent risk factors for CVD and can therefore further increase the risk for CVD. (Feingold 2023)(Paganelli 2021)(Schiattarella 2017) By providing a more detailed view of lipid-related risk factors, advanced lipid testing can help healthcare providers improve risk assessments and tailor treatment plans accordingly.

Certain organs in the body, including the heart, brain, eyes, kidneys, and blood vessels, are susceptible to damage from hypertension. If hypertension is identified during clinical assessment, evaluating for target organ damage is important for determining overall cardiovascular risk. (Shlomai 2013)

Eye health can be assessed by screening for hypertensive retinopathy. Evidence of cerebrovascular disease can involve a history of transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), stroke, or vascular dementia. Kidney health can be investigated through lab tests that assess kidney function like GFR. Symptoms such as intermittent claudication may be evidence of peripheral artery disease and damage to the blood vessels.

Combining a patient’s medical history, symptoms, physical examination, and lab tests helps evaluate target organ damage contributes to a thorough assessment of overall cardiovascular risk.

Risk assessment tools such as the Framingham Risk Score, New Zealand Cardiovascular Risk Calculator, and the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Calculator are valuable for evaluating cardiovascular risk because they provide a structured, evidence-based approach to estimating an individual's likelihood of experiencing cardiovascular events over a specified period.

These tools use various clinical parameters—such as age, gender, blood pressure, cholesterol levels, smoking status, and diabetes status—to quantify risk. They help healthcare providers identify higher-risk individuals, enabling earlier intervention and personalized treatment strategies. Overall, such tools standardize risk assessment, facilitate communication between patients and providers, and can help guide decision-making for cardiovascular disease prevention and management.

A comprehensive cardiovascular assessment typically begins with a detailed patient intake and physical examination, focusing on identifying risk factors and symptoms. This is followed by lab investigations that can include standard lipid panels and other basic tests that can assess comorbidities. Advanced lipid testing may be incorporated to provide a deeper understanding of lipid profiles and may provide further insight into cardiovascular risk.

All together, a comprehensive cardiovascular assessment enhances the ability to prevent and manage CVD through the identification of both conventional and emerging risk factors.(Flack 2020)

References

American Heart Association (AHA). (2024, January 9). Understand your risks to prevent a heart attack. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/heart-attack/understand-your-risks-to-prevent-a-heart-attack

Cheng, C., Sun, J. Y., Zhou, Y., Xie, Q. Y., Wang, L. Y., Kong, X. Q., & Sun, W. (2022). High waist circumference is a risk factor for hypertension in normal-weight or overweight individuals with normal metabolic profiles. Journal of clinical hypertension (Greenwich, Conn.), 24(7), 908–917. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.14528

Colten, H. R., & Altevogt, B. M. (2006). Extent and health consequences of chronic sleep loss and sleep disorders. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19961/

Feingold, K. R. (2023, January 3). Utility of advanced lipoprotein testing in clinical practice. Endotext - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK355893/

Feingold, K. R. (2024, March 31). The effect of diet on cardiovascular disease and lipid and lipoprotein levels. Endotext - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570127/

Flack, J. M., & Adekola, B. (2020). Blood pressure and the new ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines. Trends in cardiovascular medicine, 30(3), 160–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2019.05.003

Herink, M., & Ito, M. K. (2018, May 10). Medication induced changes in lipid and lipoproteins. Endotext - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK326739/

Know your risk: Family history and heart disease | Heart Foundation. (n.d.). https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/your-heart/family-history-and-heart-disease

Jalili, J., Askeroglu, U., Alleyne, B., & Guyuron, B. (2013). Herbal products that may contribute to hypertension. Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 131(1), 168–173. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e318272f1bb

Mohammadi, H., Ohm, J., Discacciati, A., Sundstrom, J., Hambraeus, K., Jernberg, T., & Svensson, P. (2020). Abdominal obesity and the risk of recurrent atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease after myocardial infarction. European journal of preventive cardiology, 27(18), 1944–1952. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319898019

NIH - U.S. National Library of Medicine. (n.d.). High blood pressure - medicine-related: Medlineplus Medical Encyclopedia. MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000155.htm

Paganelli, F., Mottola, G., Fromonot, J., Marlinge, M., Deharo, P., Guieu, R., & Ruf, J. (2021). Hyperhomocysteinemia and cardiovascular disease: Is the adenosinergic system the missing link? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(4), 1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22041690

Păunică, I., Mihai, A. D., Ștefan, S., Pantea-Stoian, A., & Serafinceanu, C. (2023). Comparative evaluation of LDL-CT, non-HDL/HDL ratio, and ApoB/ApoA1 in assessing CHD risk among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of diabetes and its complications, 37(12), 108634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2023.108634

Rexrode, K. M., Carey, V. J., Hennekens, C. H., Walters, E. E., Colditz, G. A., Stampfer, M. J., Willett, W. C., & Manson, J. E. (1998). Abdominal adiposity and coronary heart disease in women. JAMA, 280(21), 1843. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.21.1843

Rodgers, J. L., Jones, J., Bolleddu, S. I., Vanthenapalli, S., Rodgers, L. E., Shah, K., Karia, K., & Panguluri, S. K. (2019). Cardiovascular Risks Associated with Gender and Aging. Journal of cardiovascular development and disease, 6(2), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd6020019

Schiattarella, G. G., Sannino, A., Toscano, E., Giugliano, G., Gargiulo, G., Franzone, A., Trimarco, B., Esposito, G., & Perrino, C. (2017). Gut microbe-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide as cardiovascular risk biomarker: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. European Heart Journal, 38(39), 2948–2956. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx342

Shlomai, G., Grassi, G., Grossman, E., & Mancia, G. (2013). Assessment of target organ damage in the evaluation and follow-up of hypertensive patients: where do we stand?. Journal of clinical hypertension (Greenwich, Conn.), 15(10), 742–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.12185

Vaccarino, V., & Bremner, J. D. (2024). Stress and cardiovascular disease: an update. Nature Reviews Cardiology. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-024-01024-y

Wofford, M. R., King, D. S., & Harrell, T. K. (2006). Drug-induced metabolic syndrome. Journal of clinical hypertension (Greenwich, Conn.), 8(2), 114–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-6175.2006.04751.x

Yang, A. M., Lo, K., Zheng, T. Z., Yang, J. L., Bai, Y. N., Feng, Y. Q., Cheng, N., & Liu, S. M. (2020). Environmental heavy metals and cardiovascular diseases: Status and future direction. Chronic diseases and translational medicine, 6(4), 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cdtm.2020.02.005

Yim, G., Wang, Y., Howe, C. G., & Romano, M. E. (2022). Exposure to Metal Mixtures in Association with Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Toxics, 10(3), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics10030116